“Czyn Społeczny” Collective

“Czyn Społeczny” | Present

In 2019, we started an activity consisting in joining social work activities organized by local communities in small towns. We join in common work, e.g. cleaning up parks, building playgrounds and sport field or painting fences. We document these events along with the accounts of people who often also remember social activities from the communist era. We are interested in the positive reception and continuation of the tradition of this kind of “social work” in the peripheral communities and its collective character as opposed to individualism, promoted after 1989 in neoliberal Poland.

In 2019, we started an activity consisting in joining social work activities organized by local communities in small towns. We join in common work, e.g. cleaning up parks, building playgrounds and sport field or painting fences. We document these events along with the accounts of people who often also remember social activities from the communist era. We are interested in the positive reception and continuation of the tradition of this kind of “social work” in the peripheral communities and its collective character as opposed to individualism, promoted after 1989 in neoliberal Poland.

Katarzyna Różniak, Tytus Szabelski, citizens of Rajcza and Kunowice

***

Kolektyw Czyn Społeczny | Park 1963–2019 (2019)

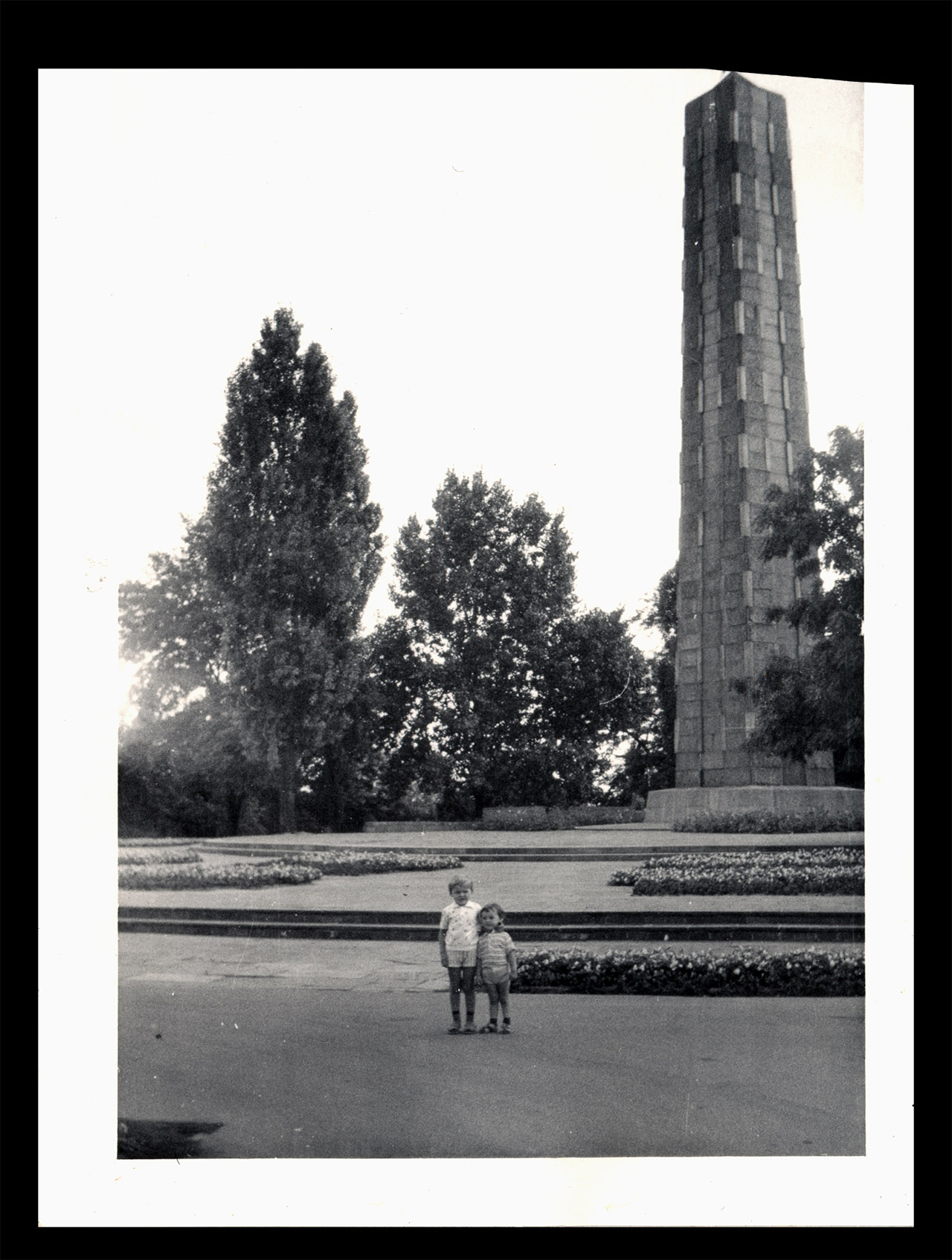

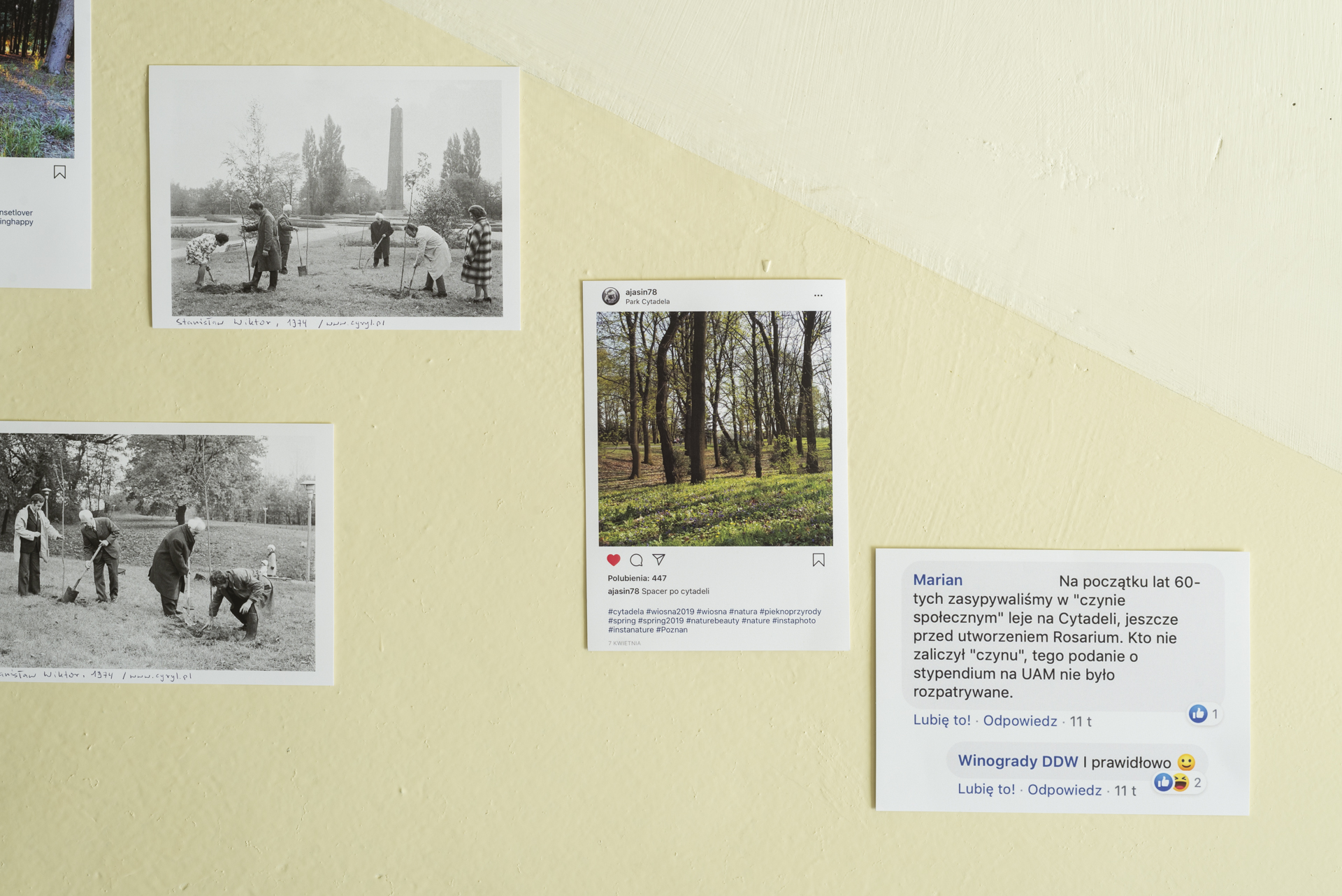

The Park-Monument of the Polish-Soviet Friendship and Brotherhood in Arms was being developed since the 1960s, mostly in compulsory social service by the citizens of the city of Poznań. The place it was established in was long intended to be a part of the city’s system of green parks, and after the war it was given a political meaning. The spatial organisation, expressive aspect and development was negotiated between urbanists, designers and artists taking part in the Poznań Sculptural Meetings (1968 to 1970). The ultimate shape of the park was an effect of tensions resulting from its double status: at the same time it was both a monument which worked for the official state propaganda, and a socially useful, egalitarian space. We were interested in the perspective of its users.

For a few weeks we were collecting old photographs from family albums and contemporary images found on social media. We were asking about people’s memories related to the Park-Monument. It was a story of common work for a socially useful goal and of using egalitarian space. It was also, but only to some extent, a story of contesting the political dimension of the park. We present the memories of the users of the Park in the interiors of a nearby apartment block in the Winogrady housing estate, but also in the very space of the Park. We used a popular children’s game called “Secrets”, hiding a few images under glass between the park’s trees and bushes.

We try to bring back the social history of the Park as a monument and propose to treat all of the space, including trees and other plants, as an alternative form of commemoration. In contemporary, constantly commercialising, capitalist city, a space like this may symbolise such values like equality and community, recall the social bounds (even if they were developed during the compulsory social service), and turn attention to the close relation between people and the natural environment. Memories of the local community, its common work and family lives is written in every single tree, as the trees are remembered by the local people. We think that the form of a park-monument, nevermind its political history, may be a clue that will help finding a more empathic, horizontal form of commemoration.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Park-Monument of the Polish-Soviet Friendship and Brotherhood in Arms was being developed since the 1960s, mostly in compulsory social service by the citizens of the city of Poznań. The place it was established in was long intended to be a part of the city’s system of green parks, and after the war it was given a political meaning. The spatial organisation, expressive aspect and development was negotiated between urbanists, designers and artists taking part in the Poznań Sculptural Meetings (1968 to 1970). The ultimate shape of the park was an effect of tensions resulting from its double status: at the same time it was both a monument which worked for the official state propaganda, and a socially useful, egalitarian space. We were interested in the perspective of its users.

For a few weeks we were collecting old photographs from family albums and contemporary images found on social media. We were asking about people’s memories related to the Park-Monument. It was a story of common work for a socially useful goal and of using egalitarian space. It was also, but only to some extent, a story of contesting the political dimension of the park. We present the memories of the users of the Park in the interiors of a nearby apartment block in the Winogrady housing estate, but also in the very space of the Park. We used a popular children’s game called “Secrets”, hiding a few images under glass between the park’s trees and bushes.

We try to bring back the social history of the Park as a monument and propose to treat all of the space, including trees and other plants, as an alternative form of commemoration. In contemporary, constantly commercialising, capitalist city, a space like this may symbolise such values like equality and community, recall the social bounds (even if they were developed during the compulsory social service), and turn attention to the close relation between people and the natural environment. Memories of the local community, its common work and family lives is written in every single tree, as the trees are remembered by the local people. We think that the form of a park-monument, nevermind its political history, may be a clue that will help finding a more empathic, horizontal form of commemoration.

“Czyn Społeczny” | Monuments

During the coronavirus pandemic, we started the third cycle of activities, which will consist of laying flowers under the monuments dedicated to public utility occupations, created during the communist era. First we laid flowers at the Nurse’s Monument in Wrocław. The inscription on the sash says “Decent wages and working conditions”. Erected in 1974, the monument is the only symbolic representation of this professional group in the Polish public space. This fact alone says a lot about the way we have valued the work of people without whom our society would not be able to function. It was only during the coronavirus pandemic that we began to appreciate nurses, doctors, paramedics and other health care workers.

Katarzyna Różniak, Tytus Szabelski, in cooperation with Iwona Ogrodzka